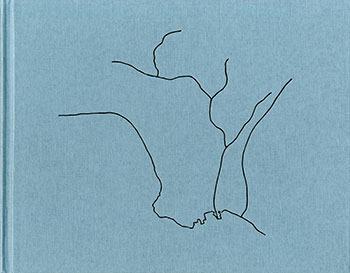

LOS ANGELES: LANDSCAPES OF FOUR ECOLOGIES

Mark Ruwedel

MACK, 2023

ISBN 978-1-915743-14-5 Hb

So many of the world’s great cities are celebrated for their rivers, but as Mark Ruwedel reports, one in four residents of Los Angeles don’t even know their city has a river. His new book about the LA River and its tributaries is unlikely to entice many of those who don’t know it to seek it out. This is not a river to swim in, to stroll beside, to marvel at, or gaze across in a state of charmed contemplation. It is presented here as a polluted mess.

For most of the year the river runs either dry, or as a low sluggish stream, but it can turn into a torrent in winter, and after destructive flooding in the 1930s it was channelised and now runs between concrete embankments for much of its length. The book’s title echoes Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), an account of the city’s culture which had little to say about nature. Ruwedel claims to detect four natural ecologies within the region – the ocean edge, the hills bisecting the city, the eastern desert and the transition zone between desert and the LA basin – but these zones are not easily distinguishable in the book (at least, not to me), which is structured instead in terms of seven linear sections of river, and focuses on the terrain and vegetation along the river’s course and the refuse and other detritus that lies scattered everywhere. The book is presented as Volume 1 of a larger series, Rivers Run Through It, although details of future volumes have not yet been released.

Ruwedel is known for his documentary, mainly black-and-white, landscape photographs of the American West, and previous books have followed the 20th century American realist landscape tradition in depicting visual and cultural curiosities within urban and peri-urban landscapes in elegant formal arrangements, rich in intriguing visual detail. The new book seems to take a new direction, in what appears to be a determined effort for the most part to avoid pleasing affect, and to seek out what is damaged, ugly and repellent. There are exceptions, pauses, that offer some transient relief. But picture after picture depicts scrappy land and vegetation, cluttered and festooned with fly-tipped or river-borne rubbish, mainly depicted in a flattish mid-grey tonality with burned-out skies and no attempt to prevent detail at the tops of pictures from evaporating in over-exposure. Frequently we are confronted by barriers and screens of ragged trees or other obstructions, preventing forward projection into or through the image. Many images repel the viewer’s gaze.

Some glimpses of the LA River given by this book: it opens with a picture of a cowboy-looking figure in a white hat and checked shirt, riding a white horse away from the camera beside a trickle of river within the city zone. A highway with road signs is visible up a concrete embankment to the left. The image looks like it was made in early morning light. It is wistful. It calls to mind the American West of the imagination, especially the Hollywood imagination, and the appeal of freshwater to anyone crossing the drylands of the interior; and yet what is to come? What kind of nourishing wholesome river will this be?

We move, a few images later, to a view from the river bed. It is wide and dry, its concrete embankment to the right. Desiccated, twiggy low shrubs grow out of the cracked earth. They looked burned. The bed is crossed by a huge flyover, deserted of vehicles, utterly still, under parching sun and a featureless sky. It is an apocalyptic image, a vision of what could be a dead near-future world, dried up, destroyed, when the water finally ran out.

An old battered tree, with broken branches and multiple healed lesions on its trunk, stands on a scrappy, twig-covered patch of earth. A soft toy frog, near-invisible, has been placed high up on its trunk, fixing us with its backward-turned gaze. Beside the frog is a near-illegible hand-scrawled sign, that seems to read: Bewar[?] of F[…] Dog. P.S. Fuck […].

In the midst of the city, another tree is wrapped to the top in water-borne reeds, the remnants of some past violent deluge. Flattened reeds cover the ground. The particular configuration of trunks and a branch propped at its base gives this tree a strange anthropomorphic appearance, a mythical figure with long hair and ragged clothing, a green man or outraged spirit of the river, arms raised to heaven, striding away in horror from the wreckage we have made of the natural environment. Meanwhile in the background, LA apartment blocks stand on the ridgeline beyond, disappearing into heat-haze and over-exposure, serenely disconnected from the drama in the foreground.

In the book’s final image, an abandoned dining chair stands upright in a wild overgrown mix of weeds with sunflowers under a willow shade, with a road bridge and concrete banks behind: a counter-pastoral image, a mocking invitation to sit and enjoy the pleasures of this dystopian world.

The logic of Ruwedel’s choices is underlined by a very different image of the LA River which appears in his earlier book, Seventy Two and One Half Miles Across Los Angeles (2020). A close-up of a flyover crossing the river, taken from mid-stream, formally balanced, tonally rich, it seems to interpellate us to admire the bridge’s architecture, the curve of the underside of the arches, its delicate pediment of railings. It belongs to the present book in terms of subject matter; but it could not possibly have been included, as it would have undermined the book’s determined focus on pollution and neglect.

In The Heroism of Vision, Susan Sontag quotes Walter Benjamin on photography’s tendency to aestheticise all that it touches. The camera, he declared in 1934, ‘is incapable of photographing a tenement or a rubbish heap without transfiguring it’. This book suggests that may not always be the case. |

|